Why Don’t We All Become Anarchists? |

|

|

Last night, while I was returning home by bus, I saw a young boy drawing the sign of anarchists, the A inscribed in a circle, with a black marker on the white side-surface of the bus. The kid was a 20-year-old, more or less. I didn’t tell him anything, figuring it would be futile. I wondered, however, if he understood what the meaning of the symbol that he drew is. What would happen in the young boy’s life if tomorrow his society were modified in the way the anarchist theoreticians dream of? I find that no philosopher, whether anarchist or otherwise, answers this question correctly; and the reason is that in order to answer it one needs knowledge that was missing until relatively recently. All the theoreticians of anarchism were born, raised, and developed their ideas before the knowledge that I will present below became available, and before the intellectuals of the world had enough time to assimilate that knowledge. First, allow me please to introduce myself. Because I will make some claims against the idea of anarchy, it is possible that the reader might categorize me automatically among those who “support the system”, the status quo, the “ruling class”. But I’m not one of those. In older times, when I was at around the age of the kid in the bus, I would categorize myself among the “leftists” — not communists, however, nor any other political ideology. I thought I was just... “a leftist”; generally, like that. Later I realized that what I am cannot be described by any of the existing political labels. I am, I would say, a “defender of the weak”, and actually I’ve been such since my early childhood! This was the characterization my mother used for me once when I was a 6- or 7-year-old boy, to justify my behavior to another mother. I don’t remember exactly what I did, but I think I saw another child doing something unjust to a third child, and I sided with the latter. This pattern continued throughout my life to date. Now, because in my country the ruling class has traditionally been the right-wing and capitalists, and because therefore the leftists were the supporters of the unjustly-treated–oppressed–have-nots, etc., I erroneously identified the notion “defender of the weak” with the notion “leftist”, that’s all. If I had lived in the Soviet Union during my childhood where the leftists had the upper hand, I think I would characterize myself a “rightist” (wrongly again). However, I talked about myself a lot. My purpose is to talk about anarchism, not about me. Whoever wants to learn what I have worked on in my life so far, can visit my home page. Anyway, I hope you understood, in case you are an anarchist, that my purpose is not to perpetuate the existing system, but to reveal the — unbeknown to you, I suspect — consequences of anarchy and anarchism. Before we start, let’s keep note of something that’s probably well-known: the notions “anarchy” and “anarchism” denote several and differing systems of ideas. Just because two people proclaim themselves “anarchists” doesn’t mean they must agree in many things. However, there is a fundamental core of ideas that, if not shared by a person, then the label “anarchist” probably does not suit them. I think this core of ideas is expressed quite well in the following excerpt from the Greek Wikipedia page for the entry “Anarchism”:

It’s impossible that the kid in the bus has read the above — I’d be damned if he has read anything at all, ever — but perhaps he is vaguely familiar with these ideas from the discussions between “theoreticians” and other wise men that he overheard in the cafés of Exarcheia Square(*) in Athens. I’ve never talked to the said gurus, but I don’t think I missed anything, because I’ve read the real theoreticians of anarchism, from philosophers to politicians — those who were not assimilated by the Establishment. However, whoever is opposed to anarchism must, I think, take seriously into consideration Noam Chomsky’s words:

Indeed. I agree. Although I do not

defend any institutions, I agree that I must demonstrate

with powerful argument that... what do I want to

demonstrate, really? The following:

Note that when Chomsky uses the term “anarchy”, he doesn’t mean the complete abandonment of authority. In other words, he would agree with the first sentence in the cyan frame, above. He and other “sophisticated anarchists” want radical changes in corporate structure that imply less control in people’s lives, not no structure at all. Of course, for us Greeks this sounds a bit oxymoronic, because we’re very familiar with the meaning of the word “an-archy” from our language: it means the lack of authority.(*) Chomsky himself, being an eminent linguist,(*) is certainly very familiar with the etymology of “anarchy”, but other Western “sophisticated” anarchists probably do not have much problem with the word, which for them means what they want it to mean. However, in the main part of the present text I argue against a kind of anarchy as it is understood by the overwhelming majority of anarchists in Greece, and, I suppose, in other nations of similar living standards; i.e., I criticize the complete lack of authority, the an-archy as it is understood in its original, literal meaning. Near the end of the text, after the main argumentation against “crude anarchy” is all exposed, I pose a question for the more sophisticated, Chomsky-like anarchists to consider. (See section “Answering Chomsky”.) Also, I know quite well that what I claim in the cyan frame is not new; others have made similar claims in the past. The difference is that none among those who supported this view stated clearly why it is correct, why the catastrophic events that I mentioned would happen. To understand why, we must take a short tour in our prehistory (all of which is based on J. Diamond’s work, “Guns, Germs, and Steel”, about which more will be said soon). Lacking this knowledge we will continue doodling little circles on buses, without understanding the consequences of the ideas we support. So, we begin the tour with the observation that will make happy all anarchists, all over the globe:

Would you like to picture that 95%? Then take a look at the following blue-and-red line:

The blue part is the time interval during which our ancestors were living according to the principles of anarchism (roughly as they are described in Wikipedia), whereas the red part is recent times, with the social classes, laws, armies, cops, and all those that cause anarchists to feel that their ideology has some raison d’être. As you see, the blue doesn’t change sharply to red; there is a transitional (indeed, long) “purple” period. To make things more concrete using numbers, the overall length of the above line (blue and red together) is about 200,000 years. That’s roughly for how long we have existed as the species that we are now, Homo sapiens. One should not interpret the number 200,000 as an exact one, because there was never a beautiful day when the first Homo sapiens appeared on Earth. Instead, there was another transitional period, somewhere around 200,000 years ago (between 250,000 and 150,000 more likely), during which our ancestors were changing from the previous species, Homo erectus, into the present one, H. sapiens. Also, at no time there was a single, lone ancestor of ours (or a single couple, according to religious tradition). There were always several tribes, which roughly are estimated to include between 10,000 and 20,000 individuals. And the location where they lived was East Africa, where today there are the nations of Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, etc. (see figure). Note that more recent findings have enlarged substantially the area of this possible region. |

|

Those of course were not the only people on Earth back then. There were, dispersed in the “Old World” (Africa, Asia, and Europe), individuals of our ancestor species H. erectus, one branch of which were the Neanderthals. Those ones used to be in Europe and the Middle East. But our ancestors were living exclusively in Africa, and only later, between 90,000 and 80,000 years ago, did they start the great exodus that led them to all the latitudes and longitudes on Earth (to Australia at around 65,000 years ago, and to the Americas between 13,000 and 12,000 years ago). Some tens of thousands of years later, after our ancestors dispersed in the world, the H. erectus humans were extinct, either due to warfare with “our people”, or because they couldn’t manage to find food easily anymore, because “our people” were more efficient at finding it. The cause is unknown to date. The last Neanderthals lived between 30,000 and 25,000 years ago. Recent evidence showed we might have a few “Neanderthal genes” in our DNA’s, which means that some of the Neanderthals are also among “our ancestors”, at least up to a certain degree. |

|

All these are facts, and have been verified both through fossil evidence, and through DNA research. Today, there is practically no reason to doubt the above. But is there any connection of all this with anarchy? Oh yes, there is. Be patient, let’s move on. The red part of the earlier colored line represents the most recent 10,000 years. We’ll soon see which earth-shattering event occurred there, in the purple part, which led us to the red one, but now let’s concentrate on the long blue part, which is of special importance to us, because as I said above it’s the “anarchic” stage of our existence. Why do I call it that way? How were our ancestors living back then? They comprised, as I said, various tribes, and the way in which they led their lives today is called “the hunter-gatherer stage”. This means that men were the “hunters” (don’t imagine anything like hunting with bows and arrows, those were invented in the last 60,000 years; nor any dogs, since humans started domesticating the wolf in the last 50,000 years, and only where wolves existed; stones and clubs were the early hunters’ only weapons). And the women were the “gatherers”, i.e., they were staying at the tribal camp (which moved from place to place over the years), and were collecting both the game that men brought to them, as well as plants (seeds, etc.) that they were gathering by themselves. (Men, too, would often bring plants, roots, etc., as a result of their “hunting”, it wasn’t always meat that they would bring.) Women were responsible for distributing the food to the members of the community, and of course with the raising of the children. Men and women had approximately the same social status; the system was neither strictly patriarchal, nor strictly matriarchal. How do we know all this? Simply, because this way of life is still in existence. There are still hunter-gatherers in many places of the world, such as in the Amazon jungle, in sub-Saharan Africa, on several islands of the Indian and Pacific oceans, and elsewhere. Anthropologists go and observe the way of living of those people and announce their findings in journals and conferences. Their observations almost always require confirmation by other, independent teams, before being accepted as facts. So we make the reasonable assumption that today’s few hunter-gatherers have not changed their way of living in some essential aspect, and thus we get a glimpse of how our ancestors used to live by observing some of their modern descendants. Note that this assumption is not unreasonable at all. As the world changes, it doesn’t change everywhere simultaneously, because there is no reason for such global-scale change to happen. The world changes only where conditions are ripe for change. Meanwhile, the older ways of living continue to exist where the conditions for change were never met.(*) Now, regarding the “governing system” of the hunter-gatherers, we can’t really talk about such a thing because there is no central authority, no police, nor judges, nor prisoners, nor guards. And the reason why all these do not exist is very simple: because no one has food available to feed them. At the hunter-gatherer stage every member of the tribe works for the food they consume, and for that only. They don’t work to feed anybody else (save for their children, and for the fact that they share their food with the rest in the rare event that there is plenty of it). Consider, how does a lawyer feed him/herself today? Do they produce the food they consume by themselves? Of course not. The lawyer produces and sells “air”. Ditto for the judge, the insurance agent, the military officer, and the computer programmer. This doesn’t mean that the work of those people is useless! Of course it is useful because, due to the way our society is organized, some people are interested in using this “air”; indeed, some people depend entirely on this “air”. But in the hunter-gatherer’s society the selling of “air” has no luck. The intra-societal micro-conflicts are resolved in an elders’ council, and that’s all. Note that there are micro-conflicts only, since there are no large properties, hence no large interests either. Please read once more those two paragraphs from Wikipedia at the beginning of this text now, and tell me if they don’t agree to the tee with the description of the hunter-gatherer’s society. Now, you might think that we could have an anarchic society without becoming hunter-gatherers ourselves. Or could we? Don’t hurry to reach conclusions, please read further. Let’s see what the earth-shattering event was, which happened around 10,000 years ago, and led the human population to develop classes among its ranks, leave the hunter-gatherer stage, and grow immensely, so that from a few hundred thousand individuals to reach several billion in our times. To appreciate what “from a few hundred thousand to several billion” means, and since a single picture is worth a thousand words, look at the diagram below, which shows how human population grew in the last 150,000 years.

Time runs along the horizontal axis, so that -150,000 means: one hundred and fifty thousand years before Christ. The number 0 corresponds to the year 1 A.D. or 1 B.C. — it makes no difference — and the “present” is at the rightmost edge. Our population is on the vertical axis. So we see that the population was nearly zero (coinciding with the horizontal axis) for the best part of our existence as Homo sapiens, started rising a few thousand years B.C. (blue corner, on the right), and reached unprecedented heights from there on, growing exponentially. What happened and caused this explosion? The thing that happened was the gradual passage from the hunter-gather to the farmer mode of subsistence. (And when I say “farmer” I include animal husbandry; simply, because there is no single word that includes both farming and animal husbandry, we talk about “farmers”.) The transformation was, as I said, gradual; that is, it did not happen that a hunter-gatherer woke up one day and thought: “What a beautiful day today! Instead of hunting, I think I’m gonna plant some seeds!” No. What really happened, most probably, is that in some places of the world where the conditions were suitable — we’ll see which those places were — people (women, most likely) observed that seeds which fell on the ground from the collection process sprouted after some time and yielded more seed. It must have taken thousands of years for the practice of planting in each family’s “private garden” to be developed and become systematic harvesting of an entire field, to the point that the field yielded enough food to render hunting for the family (and for the tribe in general) unnecessary. Of course, hunting did not disappear completely, it merely passed into the backstage. The hobby of hunting in our days, which can only damage the fauna of a place, is a vestige of this ancient mode of living of our ancestors.

Now, in which parts of the world was farming made possible? (This knowledge is not necessary for the understanding of how we passed from the anarchic-classless stage to the modern class-ful one, but it is very interesting.) Converging evidence points to the region of Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq). Firstly, there is fertile soil there, in the delta of Tigris and Euphrates. Second, plants grew in the region that were the ancestors of wheat and other cereal. And third, there were also animals, which were the ancestors of modern bulls and cows (the aurochs), oxen, horses, etc., suitable by their nature to put under the yoke. Without those animals it would be impossible to have large-scale cultivation of fields, because by using merely human hands, only small expanses of land can be cultivated. In the Americas, for example, where there were no such animals, the natives cultivated only small fields. (If you watched old westerns with American Indians riding horses, forget them: American Indians learned about horses and their benefits — as well as about guns — only after the Europeans introduced those animals into the North American continent.) In sub-Saharan Africa, where bovids exist, but which cannot be put under the yoke no matter how hard one tries, there was no land cultivation at all. (Some animals remain wild by their nature; for instance, the African elephant resists domestication, whereas the Asian elephant can be domesticated rather easily.) In Asia, where there are bovids that can be domesticated, some cultivation of land took place, but there were not many suitable plants in existence (rice only, which requires special conditions). In Australia there were neither plants to cultivate, nor animals to use (kangaroos cannot be put under the yoke) so the Australian aborigines did not develop farming. In Europe, what happened is that the practice of farming spread little by little to the entire continent, starting from Mesopotamia. (That is, without human migration necessarily involved, the practice of farming as a means of sustenance became widespread.) Geographical barriers, such as the Sahara desert and the Himalayas, in addition to the lack of suitable fauna and flora, did not allow the practice of farming to spread further in ancient times. In general, we see that farming developed where there was the infrastructure of plants and animals. For reasons that will be explained immediately, farming gave a boost to the development of civilizations, which in turn spread and subdued all those other people who had “lagged behind” in development (American Indians, Africans, Australian aborigines, etc.). So it wasn’t “the intelligence of the white race” that led to the development of technology, as some believe, but the fortuitous coexistence of features of fauna and flora at some places. (No causal connection between intelligence and skin color has ever been scientifically discovered.) All the above, and much more and interesting observations are explained in J. Diamond’s seminal work, “Guns, Germs, and Steel”, a 1996 publication, for which Diamond received the Pulitzer prize. To this date, nobody has managed to counter Diamond’s arguments, which, after all, are based on fundamental observations of the natural world. Let us note in passing that Diamond’s theory answers only the general question, “Why did Europeans develop so much technologically and eventually conquered and dominated all other peoples?” But it does not answer the more specific question, “Why, among the Europeans, did the ancient Greeks develop their civilization to unprecedented levels, to the point that many of their achievements of the classic times in arts and philosophy remain unsurpassed to this date?” Diamond’s theory is moot on this question, which might be of special importance to some of us. However, interesting as the above might be, they do not answer directly our central question, which is: “Why did farming bring about the development of technology and the emergence of social classes?” It’s simple, here is why: With farming (and animal husbandry) a surplus of food is created. Whereas the hunter-gatherer secures only as much food as is necessary for daily survival (and sometimes not even that), the farmer produces quantities, e.g., of wheat, which can be stored, and can feed a larger number of hungry children. Stored food can provide nutrition to the farmer in the following year, when perhaps the crops will not be plentiful. The hunter cannot store anything: whatever is caught must be consumed, otherwise it’ll rot. Now, the farmer’s food surplus is in a position to feed not only the farmer’s children (who can be more than the hunter’s), but also members of the tribe who do not busy themselves in farming, but have other duties, such as the duty of the soldier who protects the tribe from enemy attacks. Farmers had the luxury, for the first time, to feed people who did not contribute directly to the production of food, but instead were “selling air”, such as soldiers, priests, the king and his court, the scientists of the time (e.g., the Mesopotamian astronomers, who observed heavenly phenomena and the influence of seasons on crops, or the geometers of Egypt, who could compute and rediscover the borders of fields when the latter had been covered by the mud of the Nile), the scribes (after writing systems had been invented), etc. Those “professions” were inconceivable at the hunter-gatherer stage — impossible, to be exact. But note that, at the farmer stage, many of the new professions were mandatory. For example, if you have a quantity of wheat in your storage rooms and the neighboring tribe that’s not concerned with farming is eyeing it, it’s a good idea to maintain an army unit that can defend you against the enemy attack; when the Nile floods and covers the borders of fields with mud, it’s good to have specialists who know how to compute and find again the lost borders; and so on. Also, the army units require discipline, which can be applied effectively through a hierarchy of ranks, on top of which stands the king, who is often also the religious leader (e.g., Pharaoh). It is not a coincidence that farming societies acquired kings, whereas the more anarchic hunter-gatherer ones did not know of such a title. (There can be a tribal chief or shaman among hunter-gatherers, but such a person does not have the absolute powers of a monarch.) As for police, there wasn’t any yet. There was the army, needed to impose order on the class of slaves, who were the captured people from among the neighboring subdued tribes. If a crime was committed, even during the later, classic Greek times, one was expected to find justice by one’s own power. Of course there were laws, and indeed, written ones from some point on, but the application of such laws was not a simple matter. Even today, the police does not intervene for micro-conflicts in villages (“This olive tree is mine” — “No, it belongs to me!”) although it is present. Back then, there was not even the notion of police. The crime should be serious enough for the state to intervene in some way — e.g., murder, snatching of women (who were the property of men), sacrilege of a holy place, something like that. The emergence of some form of police units is a later development, of the Roman times. Still, police did not appear suddenly, just because some insane Roman emperor envisioned it in his wild dreams, but because there were increased needs of imposing order, especially in a vast empire such as the Roman one. Without those classes of people (soldiers, policemen), the empire would collapse under its own weight. Now, one should not say, “Well, let it be, let it collapse!” But there were so many poor people whose existence depended on the existence of the empire! If their society were ruined, millions of people would die (including our Greek ancestors, mind you, since they became Roman citizens after 146 BC). Now the succession of events should be obvious. The surplus of food, initially, created classes of people who had the privilege of eating for thinking, or “selling air”, as I said before. Some among those thinking people found ways to extract metals like iron from the rocks of the earth (from which only a few soft metals, like gold, silver, and copper were extracted before, because they can be found in pure state, unlike iron, which is found only in compounds). The construction of machines became possible with the use of such metals, which were giving much greater power than before. And note that the design of machines required thought — remember Archimedes who was killed while thinking. The power of machines and thought made the development of technology possible, from the products of which our lives depend entirely today. This last phrase is the most important one in all this introduction, so allow me to repeat it, please: our lives today depend entirely on the products of technology. Now let’s see:

What would be the first thing a good anarchist would like to dismantle? A single idea comes immediately to my mind, without much thinking, appearing more or less obvious: the police! Isn’t it the police that constitutes the instrument of imposing the order of the ruling class? Is there any anarchist who disagrees with that? Fine, we dismantle the police. Let’s see what the consequences of this are. Police is the “right hand” of the

state with which the laws are implemented. Laws cannot be

implemented without policemen because, for example, it is

not enough to have a trial and a judge who determines a

sentence; someone must be in a position to force those

who were convicted to abide by the sentence. Policemen do

that. Since we dismantled the police, it’s unnecessary

to conduct trials, because everybody will be in a

position to ignore the judge’s decision, or, quite

simply, not appear in court at all. Therefore, judges, prosecutors, attorneys, and all those

who work

in the judicial system have been rendered unnecessary and superfluous.

Very well, we got rid of all those air-sellers! So we

delivered a deadly blow to the executive authority

of the state (no more cops!), and we’ve gotten rid of

the judicial authority in its entirety.

Hooray! Suppose that a muscular guy who prefers to settle his business with his physical power forms a small gang with a few other muscular guys, and one day they come to your house. They break down the door, storm in, smash and turn everything to smithereens, grab whatever they encounter and fits in the sacks they brought with them, and just so that they don’t leave you with any doubt about their intentions, they also rape all the female members of your family before leaving; perhaps they do that also to some hapless male who happened to get in their way. Pardon me, what did you say? That the above is not included in the menu of anarchy? Why? Because we read, “Anarchism [...] promotes self-management and focuses on the personal responsibility that individuals have for the effect of their actions toward themselves and toward the society of which they are members”? But, excuse me, it’s not you who decides what the muscular guy with his muscular cohorts will do. He decides. Likewise, in a chess game it is the opponent who gets to decide his moves; you don’t dictate to your opponent what moves to make! On the contrary: when you play chess you play assuming that your opponent will make the move that’s worst for you. Otherwise you don’t play real chess but some game for toddlers. And don’t tell me that in an anarchic society there will not be conflicts, because I will ask you which planet did you come from, anyway. Not only will conflicts exist, but they will even be of the worst kind, much worse than what I described above. Without executive authority, mafia will emerge, which will impose its own laws at gunpoint. Think of Russia after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, think of Sicily since centuries ago to the present, think of Chicago at the beginning of the 20th century, and you’ll probably start suspecting what kind of society without executive and judicial authority we’re talking about. And for those who didn’t get it yet (because even for the most obvious thoughts there are always thought-proof skulls that resist them), mafia means “might makes right”, it means the imposition of unwritten and cruel laws, the violation of which is usually punished by death, and all those things that directly contradict the notion of anarchy. Perhaps you think we might manage to form some small groups for our own self defense, as some have proposed, without allowing governmental (state-wise) security units to form. Well, this means simply that we organize and train our own, small, personal army, to defend ourselves against the neighboring small, personal army (the muscular guy’s), which, in the end, might prove stronger than ours and beat us. Just like in the ancient times. The right of the most powerful person will prevail. But wait, we didn’t finish with the consequences yet. We just started. At present we live in very populous societies — many of us in large urban areas — in which we take decisions that concern not only our immediate private affairs, but also our social affairs: how much I have to pay for the garbage collection, for a road that will be made in the countryside, for flood prevention, and so on. Naturally, we don’t decide directly for these matters, nor every day, but if the issue becomes urgent — if the state asks us to pay too much, for instance — there is supposed to be a congressman elected in our region who can listen to our complaints and take some action. In large urban centers, of course, congressmen can’t care less about our needs; but in small cities they listen to their voters, because a small number of voters determines whether they are elected or not. Now, in the brave new age of anarchy that has just risen, will there be any parliament? Obviously not. Parliament, that is, this all-important instrument of the legislating authority cannot exist, because what’s the point of making laws if the executive authority by which these laws are implemented does not exist? (We got rid of the executive authority, together with the judicial one, I hope you remember that, right?) Consequently, at the same time we got rid of the legislating authority. If you know some way in which we can have laws (social behavior rules, that is) without being able to implement them, let me know. Therefore, everything that concerns

decision-making for the society as a whole is tossed

away, too. You, the “good” anarchists may gather

together and take “good” decisions about yourselves,

but when the muscular guys come to the neighborhood, I

don’t know you and you don’t know me.

Fine, we got rid of all authorities: executive, judicial, and legislating. Wasn’t this the fundamental goal of an-archy? We achieved it, and indeed, with a single checkmating move: the dismantling of the police! Like a knitted sweater, which is un-knit in your hands by pulling just one thread of it. Now, the result was the establishment of the law of mafia, and maybe some of you believe that the consequences end there, and that perhaps we might manage to avoid the mafia rule with some other clever trick. Unfortunately, reality is ruthless: as you’ll see below, not only will the Mafiosi not survive, but neither you nor anybody else will. Let’s keep going. We move on now to the technological and entrepreneurial domain. You must have noticed, I hope, that during all this time I managed to give you a headache through a computer screen, which receives data by means of something we call the Internet. This thing, the Internet data, arrive at the computer you use now not through magic, but because there is a company specializing precisely at that: bringing the data to you. The company does this because somebody has paid it (you, your dad, the internet café that you paid, the public university that we all pay,(*) somebody anyway). Now, companies like the one I just

mentioned are private enterprises, and as such they

usually have an owner, or group of owners, and employees.

The employees work for the owner, who, as we all know,

exploits the surplus value of the employees’ work,

paying them just as much as they need to sustain

themselves and continue working, while he receives

the lion’s share, etc., etc. Very well... We know all

these, with the addendum that we also know one more little detail: that if there is no owner, or

if the owner is some collective organization such as some

workers’ union, or the State (as was the case in the

Soviet Union in the good ol’ times), then there is no

motivation for work, the company does not produce much,

and after some time it goes bankrupt and we all go home.

(Or, even worse, as it happened in the Soviet Union

times, the State itself goes bankrupt and it

disintegrates into its original constituents.) With this

little detail in mind, I hope we all understand that that

#%@!$@!#, the owner, who feeds from the workers’ blood

like a leech, remains at his post until further notice.

Now, suppose I am an employee at a company, and the bright first day of our anarchic life has just dawned, in the year 1 A.A. (After Anarcho-self-determination.) Why should I work for my boss? I can

very well get organized with my co-workers, and after

they also digest and assimilate the new situation in their minds, we

can all go to our boss’s office and force him to

relinquish to us the company title of ownership.

Or, even better, we can force him to sell the company by

himself and give us its value in cash. We can hold him as

a hostage, if we wish, until he does it. Who’s gonna

prevent us? The police? Ha-ha! The police ain’t no more! Perhaps I don’t sound very serious, above, but if you can think of some really serious reason for which it is not in the workers’ interests to get hold of their boss’s company, please make them known to me, so I learn them, too. I believe it might take a bit of time for the workers to really get it that they can indeed do the above without any legal consequence (legal? ha-ha!) but finally they’ll get it. And they’ll do it. At least some of them will, and when the rest see it and realize that it can be done, they’ll do it, too. And the above is not the only way in which workers can act, in the absence of police. For example, they can form a gang — even together with their employer — and go and destroy their competitor’s business at night. What one can do when consequences are absent is only limited by one’s imagination. In short, entrepreneurial activity will come to a grinding halt. But, as I already mentioned, today our lives depend entirely on the products of technology, which are the results of entrepreneurial activity. Note that when I say “technology” I don’t mean only the one of the “high tech” genre (PC’s, CD’s, DVD’s, media–shmedia), but all the products of human toil, including chairs and scissors. Even the milk that we buy is manufactured by some company — we don’t milk cows! The bread, too, which we buy from the bakery, is produced by a company: the baker’s own one. (Mr. Alekos, the baker around the corner in my neighborhood, employs around 15 people in his bakery, believe it or not.) But even the baker is supplied by flour from some company, he doesn’t grind the wheat! We don’t produce our food by ourselves anymore, we’re neither farmers (at least most of us aren’t) nor hunter-gatherers. And even today’s farmers buy their bread from the bakery; not even they produce most of their food from their own raw materials, but rely on others, on enterprises. When the entrepreneurial activity dwindles and dies out, we will dwindle and die together with it. By what means do you think the billions of people are sustained in life today, by thin air? Their food is manufactured by companies. Therefore... Therefore the overwhelming majority of the population of Earth will die of famine. Initially, only the few who possessed land and animals will survive, but even they will go through rough times, because the farming machines will stop working — who will maintain them, who’s going to build new ones? — and they will be forced either to find oxen and horses, as in the ancient times, or to abandon everything and turn to hunter-gatherers. Eventually, the survivors among us will be driven back to the hunter-gatherer stage. But we won’t survive even there, because our environment is not in a position to support hunter-gatherers anymore. Take a look around, observe how our country has become after centuries of exploitation through farming and animal husbandry: those dry, bald, rocky hills in southern Greece used to be all green in ancient times. We know this because the ancient Greek texts talk about animals like the wild boar, the bear, the lion, and others, which wouldn’t be able to survive in today’s environment because they would have nothing to prey upon. Do you see animals for hunting anywhere? Perhaps on some ridge of the Pindus Mts.,(*) yes, but how many of us can go and live on Pindus? And for how many is the game sufficient there? Further, with what shall we be hunting? Bullets are not an option, we’ll soon run out of them — remember, technology is kaput! — therefore we’ll resort to stones, bows and arrows, and to makeshift fishhooks, to catch an occasional fish, with the vitamin that’s good for the eyes.

So, what do you think? Isn’t what I described going to be the result? If not, why? Could it be that our anarchic future will actually be much brighter, and it is I who’s the benighted one? I’ll gladly listen to your opinions. But first, you’ll conclude listening to mine, because I’m not done yet. In what follows I present examples that constitute evidence (of the kind that Chomsky demanded) for the observation that all large so-called “complex systems”, like a human society of billions of people, require structures. The larger the system, the more complex the structures. And vice-versa: complex systems with a large number of members and lacking structures do not exist. Let’s move on to review the examples. |

|

The term “complex system” is a scientific one, which I will not define here, but it will become understood to whoever is unfamiliar with it through the examples that I give below. First, let’s see again what Chomsky says regarding complex systems (same source as before, my emphasis):

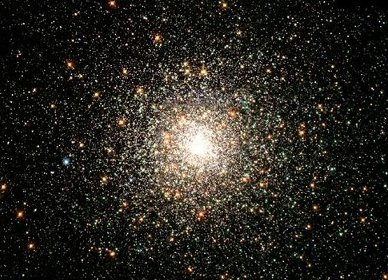

Now, although Chomsky is right when he says that we don’t understand very well (yet) the laws that govern complex systems, we can, however, see several examples of such systems and form an idea about how they are organized. I start with astronomy. A galaxy is a complex system.

Its members are stars, interstellar dust, and more

(planets, comets, asteroids, and various other bodies).

There are galaxies that are simple, with few stars (a few

hundred million), as well as enormous ones, with

trillions of stars. (Our own one, the Milky Way, is a

medium-size galaxy with about 200 billion stars.) |

|

|

|

| The Small Magellanic Cloud (credit: NASA/ESA/HST) |

Galaxy M51, otherwise known as: Whirlpool galaxy (Credit: NASA/Hubble Heritage Team) |

|

The picture on the left shows the Small Magellanic Cloud, a small (“dwarf”) galaxy, companion of our own, which lies at a distance of around 200,000 light years from us. As you see, it is structurally irregular, and indeed, “irregular” is an astronomical term assigned to galaxies without structure, typically little ones, like the Small Magellanic Cloud. Now take a look at galaxy M51, in the picture on the right, better known as Whirlpool Galaxy. It is a “spiral” galaxy, about 23,000,000 light years away, full of structures (anything but irregular, that is) made of interstellar dust (dark spiral structures), and a bright nucleus at the center, comprising billions of stars. This is not one of the largest galaxies (it’s about half as massive as ours), but is large enough to form the typical structures of spiral galaxies. Now, there is also a 10-15% of large and aged galaxies that are not spiral, but elliptical. However, “elliptical” is one thing, and “irregular” (anarchic) is another. Elliptical galaxies have a definite shape (of an ellipsoid, or sphere), possess a nucleus and structures like those described immediately below (globular star clusters), contrary to the irregulars like the Small Magellanic Cloud. We encounter this pattern, i.e., small–unstructured systems versus large–structured ones, again and again in nature. (And don’t make any association with left–right; I arranged the pictures thus on the page without any political idea in mind!) Look what we see if we zoom into the

structures that exist in a galaxy. We find star

clusters there, that is, groups of stars, some of

them small, some others medium or large. |

|

|

|

| M45, the Pleiades (credit: NASA/ESA/HST) | Globular cluster M80, in Scorpio (credit: STScl/NASA/ESA) |

|

Take a look now at the “globular cluster” M80, in the constellation of Scorpio, at a distance of 32,000 light years. In spite of its distance, it is a structure within our galaxy. Globular clusters, which are called like that for obvious reasons, are spread throughout a large sphere that contains the galactic disk, and include hundreds of thousands of old stars. (The reddish color in stars reveals an old age, whereas young stars are bluish; our middle-aged Sun is yellowish if seen from some distance — because seen from up close it’s blindingly bright and so it appears white.) We see that globular clusters, with a large number of stars, show clear signs of structure, with a nucleus at the center and a density that tapers off toward the edges. But even if we focus our attention on

an individual star, we’ll observe the same pattern

again. |

|

|

|

| Interstellar dust (from the nebula around eta Carina, visible from the southern hemisphere: STScl/NASA) |

Our Sun: condensed large quantity of interstellar dust (artificial image, made by the program Celestia) |

|

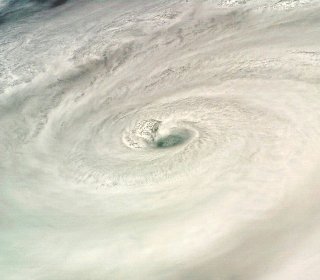

Can we zoom in

for one last time in the context of astronomical

examples? Let’s move to a short distance from our

planet, so much that we now make a brief foray into the

domain of meteorology. |

|

|

|

| Sparse clouds, as they appear from satellite | Denser clouds (cyclone) from satellite |

|

All

right, we’re done with the heavenly examples, let’s

move now to some “down to earth” ones — quite

literally. Indeed, let’s go to a great depth, at a

magnification of thousands of times, to see some

biological creatures. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

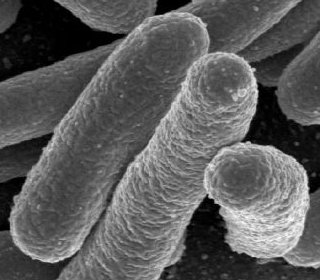

| Above: bacteria of the species Escherichia coli (credit: U.S. National Institutes of Health) Below: structural diagram of a bacterium |

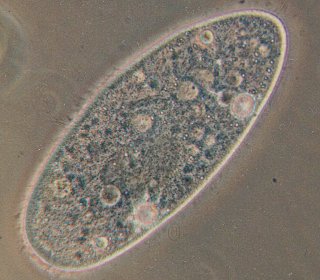

Above: eukaryotic cell (paramecium) (credit: GNU license) Below: structural diagram of a eukaryotic cell |

|

Then, something happened. In the course of a couple billion years bacteria were gradually changing the constitution of the atmosphere of the Earth, making it richer in oxygen. Owing to the larger oxygen content, the appearance of larger cells (still bacteria) became possible, which, having more volume, needed more oxygen for their metabolism. At some time, some of these large bacteria engulfed smaller ones, but they didn’t digest them, but kept them within their bodies. This was beneficial to the larger bacteria because the internal small ones became the factories of energy production for the larger ones. In the diagram, on the right, you see the large cell; and inside it, those blue ones with the little yellow “worm” are the smaller bacteria, which are called mitochondria. The “worm” is the DNA of the mitochondrion. We, and all animals, manage to move around thanks to the mitochondria of our cells. (Plants generally don’t have mitochondria, but chloroplasts.) But there are plenty of other organelles in a eukaryotic cell, that is, the one that “has karyon”, or nucleus. It is the nucleus that contains the DNA that, more or less, determines what you look like, and is half from your dad, and half from your mom. (The other one, the DNA of the mitochondria, comes exclusively from your mom.) Anyway, to make the long story short, the eukaryotic cells on the right are much larger, and much more complex compared to the prokaryotes, the bacteria. Paramecium, for example, which we see in the picture on the right, can reach up to 350 μm, or 0,35 of a millimeter (0.22 of 1/16th of an inch), which means that it can be seen with the naked eye! In general, a eukaryotic cell can be 1000 times larger than a bacterium. The pattern remains invariant: the larger kind of cell is definitely more complex in structure. If life forms prior to the bacterial stage had survived, then we’d see an even more anarchic organization, with little or no structure. Note that cells are “complex systems” in the sense that they are made of organic molecules; those are the basic building blocks of the cellular system, the molecules, just as the basic building blocks of a galaxy are the stars. We zoom out now, to

observe some species of animals. Do you think that the

same pattern would be observed there, too? Well? Guess! |

|

|

|

| Poripher (sponge) | Vertebrate (owner of that sponge) |

|

In due time, animals evolved. It’s not that they just grew bigger (there are animals much smaller than a sponge), but that they started exhibiting more complex behaviors. For example, most animals move by themselves, and motion usually implies some characteristics (shape of body, maybe fins, maybe legs, maybe wings, usually eyes, etc.). The more behaviors an animal can exhibit, the more complex its body is, generally. This doesn’t mean that animals were becoming more complex as the millions of years were passing by, but that they were “exploring” (while evolving) more and more environments. The picture on the right shows a well-known kind of animal, quite banal with respect to its biological characteristics, but capable of writing the present text. Ideally I should put up there an animal with visibly more complex structures, like a tarantula, but I didn’t have enough horizontal space to do justice to the exquisite structures of the tarantula, so I ended up using my boring self. Anyway, the advantage is that you are very familiar with the structure of the above yellow-bluish animal: it has a skeleton, internal organs, external parts (limbs, head), circulatory system, digestive system, respiratory system, endocrine system... it’s complex, in short. Well, let’s say so. Definitely more complex than a sponge. Now, you might be wondering, in what sense are animals “complex systems”? All right, galaxies are made of stars; cells of molecules; what about animals? Why, they’re made of cells, of course. In animals–anarchists, like sponges, it happens that their cells hardly form anything at all. In animals like the vertebrates (us, for example), the arthropods (such are the spiders), and many more, cells form complex structures. Finally we reach the kinds of complex

systems in the realm of biology that correspond exactly

to our subject: animal societies. Humans, of

course, are also animals from a biological standpoint,

and their society is a “society of animals”.

(Granted, some of us, besides biologically, are also “animals”

figuratively, but let us ignore this for now.) But we won’t

examine human societies here, because we reviewed their

development (however superficially) from hunter-gatherers

to the present state, in the introduction. Let’s see

examples of other kinds of societies. |

|

|

|

| Wasps (copyright free) |

Ants (credit: GNU license) |

|

On the right: ants. They’re “cousins” of the wasps, which rightly, I think, are called “the humans of the insect world”. Like wasps, each species creates colonies with approximately the same number of individuals. The difference is that ants make much larger colonies, in general. Some species include millions of ants in a nest. Species with small-numbered colonies are very rare, and I am not aware of species with solitary ants. (There are the solitary so-called “velvet ants”, e.g., in Russia and South Africa, but they are not ants, but wasps without wings.) Regarding our subject, there are hardly any essential differences between wasps and ants; simply, because ant colonies have larger numbers of individuals, they also possess a greater organization. There are soldier ants, whose only role is what one would expect of soldiers: defend the anthill from the “enemy”. There are hunters, who go out of the anthill and search for food in large areas around it, as well as farmer ants (not in all species, in some only), who cultivate a fungus (of the genus Leucoagaricus), which is eaten by all members of the colony. Actually, there are specialties among the farmers: some ants go and cut leaves with which they feed the fungus (that is, the fungus grows on those leaves), other ants water the fungus, and so on. If they find out that some kind of leaves is toxic and destroys the fungus, they stop bringing leaves of that kind! There are also ants that busy themselves with animal husbandry: they attend aphids (the microscopic lazy green bugs that sometimes cover entirely the buds and the fresh leaves), which they literally milk, drinking the nectar-like juice which they cause them to produce by squeezing them; also, they guard their herds from the “bad wolf”, that is, the ladybugs, which show a special craving for the juice of aphids (except that ladybugs don’t milk the aphids; they eat them). In fact, just as we have created special kinds of sheep (fat ones, long-haired ones, etc.) through selection, so ants have created some kinds of aphids particularly fat and juicy. They even have “cows with a bell”, which means they feed some other species of insects (again for their juice) which make a sound with their belly, which ants hear and locate! Naturally, there is also the queen (more than one in some species), who doesn’t have the authority of a monarch, she’s simply the sexual reproduction organ of the colony. Police? No, there is none, because it’s not needed: ants are tiny simple robots, they don’t have a personality that can make them break the law some times, and if something goes awry in the anthill there are always the soldiers who can take care of the matter. Ants have not discovered writing yet, but they have a kind of language, which works not through sounds, but through chemicals, the pheromones, which they spread on the ground as they walk, thus allowing other ants to understand where they came from and where they’re going. The most important observation for our subject is that large anarchic colonies of ants do not exist. There are either very small ones (with a few hundreds of individuals) with not much organization, or larger ones, with more organization; the larger the colony, the more structures it includes. Some scientists consider the colony of an ant species as a super-organism, one animal that is, which comprises “cells” (the ants) and “organs” (like those I described earlier: soldiers, farmers, the sexual organ which is the queen, etc.). If we think about it, human society is also a super-organism: a complex system with its own internal organization, the building blocks of which are we, individual human beings. But we tend to put this thought aside because we are accustomed to look at the world through our individualistic spectacles, even though we know we are members of a complex system that’s really a super-organism. I don’t know if Chomsky would want more evidence. I hope this is enough. |

|

So, I see two alternatives: either we continue to exist in multi-billion numbers, as at present, and with the existent structures; or we destroy the structures and become a community of a few thousand people (on the entire planet, mind you), with the organizational stage of the hunter-gatherer. This of course implies that you, dear reader, who perhaps yearns for the advent of anarchism, will almost certainly die of starvation, because the survivors will be only the few people who possess land, animals, and the experience to eke an existence from them without the least technological help. You, given that you’re reading the present, most probably lack those things. The truth, however, as I explained in the main text, might be even worse than that. Because, after centuries of exploitation, we have destroyed our natural environment, so that now it bears no similarity with the one that used to support hunter-gatherers thousands of years ago, my prediction is that the number of hunter-gatherers who will manage to survive will be miniscule. It is not hard to guess what will happen next. After a few centuries of living like hunter-gatherers, our very few descendants, having lost all contact with the previous civilization (due to the lack of technology in order to preserve knowledge in books, etc.), and having only a vague familiarity with its existence thanks to the carcasses of the once flourishing cities, will “reinvent the wheel”, i.e., they will gradually pass again to the farmer stage. They won’t have the knowledge — or rather, sorry, your wisdom, I meant to say — to realize that if their society becomes complex again they will then suffer the consequences of complexification (police, etc.), because detailed knowledge requires technology for its maintenance. Therefore, just like every complex system that grows larger, they will reinvent the wheel, by which I mean they will re-create the social structures. Back to square one. In other words, the experiment of anarchism will almost certainly end up with a big “hole in water”, as we say in Greece;(*) indeed, the grandest such hole that the human intellect will have ever achieved. Answering ChomskyBesides keeping structures as they are or abandoning them altogether, there is an obvious third alternative: reducing them — which is what those who I called “sophisticated anarchists”, like Chomsky, advocate. Could that third alternative be viable? I hope that the numerous examples I listed above make it clear that those are all self-organized complex systems. If they have the structures they have, it is because without those structures they wouldn’t exist. They simply came to be that way, with that amount of structuring. Ditto for the present-day human society, which is also a self-organized complex system. If it has the structures that it has, it’s not because some person — some sick mind — thought, “Oh! Let’s add this kind of structure to the society, and then this one as well!” Nothing like that. “Self-organization” means that the existent structures emerged all by themselves. There is no one to blame for their existence. Now, well-meaning folks like Chomsky speak like this: “[T]he burden of proof is always on those who argue that authority and domination [i.e., corporate structure – H.F.] are necessary. They have to demonstrate, with powerful argument, that that conclusion is correct.” But... there is no one who needs to “argue” for anything in a self-organized complex system. The system is the way it is not because someone argues that it should be that way, or that it should have “that much” structure (which appears too much to Chomsky), but because the system evolved like that, listening to no individual’s opinion, simply becoming like that by itself. On the contrary, Chomsky and others are individuals who argue that there should be less structure. In other words, they claim that the system wrongly evolved the way it did, and that it can make do with less structure. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I see only one side who really argues something: the side of the Chomskian “sophisticated anarchists”. The other side, i.e., the complex system itself, doesn’t have an argument, it merely is. I, for example, do not side with anyone; I merely observe a complex system that seems to keep going (for all the troubles it gives us) on one hand; and some people, those whom I call the “sophisticated anarchists” on the other hand, who are the ones who truly argue something (“Less structures suffice!”). And whoever argues anything, that’s the one who has the burden of proof. What I see is that Chomsky tries to shift the burden of proof from his shoulders to the shoulders of some nonexistent entities, because no one really needs to defend a complex system that evolved by itself to work the way it does. (If there are any defenders, they are fools; all they need to do is shut up.) The above, of course, doesn’t imply that Chomsky is wrong; it merely says that Chomsky is the one who has the burden of proof. Could Chomsky, however, be right? Could less structure still suffice for human society? If I had to bet my money somewhere, I would bet it on the “Chomsky is wrong” side, reasoning like this: In mathematics, when we want to see if a proposition is right or wrong, we often resort to the trick of “Let’s see what happens in the limiting case.” Whatever happens in the limiting, extreme case, usually also happens in the less extreme, common one. For example, if you have a triangle and want to see if its three angle-bisectors meet at a single point (assuming you don’t already know this elementary fact), you may try to draw an extreme kind of triangle (e.g., one with a huge obtuse angle and hence two other very sharp ones) and see how the three angle-bisectors behave. (You’ll find that they do meet at a single point, hence you’ll be reassured that this is true also in the general case — though you’d need to prove it if you wanted to be absolutely sure.) The same reasoning leads me to suspect that Chomsky is wrong. The “extreme case”, in our case, is the one I discussed in the main text up to this point: the complete lack of structure, the chaos (ΧΑΟΣ) as Greek youngsters express the idea on the walls of Athenian buildings. That idea, I argued, would result in the demise of humanity as we know it, and I hope I brought ample evidence for it. This extreme case suggests to me that if the structure was not nonexistent but less, then there wouldn’t be a total demise of the complex system of human society, but the system would suffer injury; the greater the loss of structure, the greater the injury suffered. And when I say “suffered injury” I mean that, in practice, some people would die. But mine is merely a suspicion. I’m not posing an argument, I am only an observer. Chomsky and the other sophisticated anarchists who pose their argument are the ones who have the burden of proof to show that less corporate structure can still result in a viable system, without a consequent loss of human life. I’ll be waiting for their proof. Readers’ ReactionsLooks like I was wrong in my initial prediction that no anarchist will ever read this page. Judging from my correspondence, anarchists, ex-anarchists, and many others, including some friends of mine, went through the text and sent me their valuable reactions. I will focus on criticism below, because I don’t see any value in mentioning the praise.

I would like to state as categorically as possible that I don’t assume that human nature is evil. On the contrary, I agree that, on average, humans are good by nature, and in my treatise on religion I proposed an evolutionary explanation for the observation that evil-doers are a minority, not a majority (see §2.1: Biological Foundations of Morality and its Evolution). So why do I still think that human society will collapse without police, in spite of the good nature of most of its members? Because it doesn’t matter whether 99% of the population behave like saints, loving and supporting each other, and opposing evil with all their good-natured hearts. It suffices that there is a remaining tiny percent of evil-doers. Those evil-doers are the ones who, in the absence of police and enforcement of societal order, will take advantage of the situation and accumulate power through the build-up of their personal arsenals. While the peace-lovers will be minding their peaceful businesses, the war-lovers (few as they might be) will engage themselves initially in an arms-race without an opponent. Why? Because that’s how war-lovers behave: they act so as to eventually dominate over others. Will there be any war-lovers in an anarchic society? Couldn’t there be only good-natured people, socially well-behaving ones? Hmm... let me see... you were raised on planet Earth, right? Next question, please. And what about the point that evil-doers are few, hence their number is dwarfed by the majority of good, responsible individuals? Well (dear utopists and day-dreamers), open your eyes and see what has happened in the past, up to the present: history is replete with examples of small groups of people who dominated over much larger masses, merely because such minorities acquired weapons and military power:

It’s always like that: a minority of well-armed people suffices to dominate and dictate their own rules to a much larger majority. That’s why, in an anarchic majority of well-meaning, good-hearted, and peace-loving people, the mafia will dominate. If you believe otherwise, I’m ready to bet you also believe in Santa Claus.

This remark espouses the same utopian spirit as the previous one: “Oh, let’s all be following societal rules not because they’re imposed on us by authority, but because we learn by education that that’s the right way to live.” My friend, I wholeheartedly agree with you: that’s the way it should be. But conflating our desires with reality might be the explanation for why the idea of anarchism persists. If you manage to point to me a society in which all people, without exceptions, agree to play by your societal rules (of mutual respect, cooperation, etc.), then I’ll agree that you found a society in which anarchism can be applied, temporarily. But temporarily only: even such a hypothetical society, after losing its ability to invent and manufacture cutting-edge weapons, will soon become prey to neighboring societies (or nations) that didn’t apply anarchism to themselves — unless you assume that the entire world will pass into the anarchic stage simultaneously, as if by magic. Knowing that you have traveled a bit outside of the U.S., and thus you’re aware of what the rest of the world looks like, I can’t imagine you have such a pipe dream in your mind. More likely, you’re trying to make me agree that voluntary rule-following is much preferable than coercion and authority, except that you’re preaching to the choir: I agree with you, that’s the right way to behave socially, but in the end it doesn’t matter what you and I believe and desire, but what is out there. And “out there” is the human society, a complex system that works with its own laws, which we cannot change no matter how hotly we desire it. We can’t change the fact that some, a minority of people have a personality hardwired in a way that urges them to try and dominate over other people. That won’t change. And it is those few who will ruin your recipe for an anarchic society, independently of whether you and I grew up in non-authoritarian environments.

I am saddened to say this next, but it looks like you didn’t read my text carefully enough. I took some pains in the beginning to explain that this was written with the Greek (and other European) anarchists in mind, who indeed oppose all structure. A word that appears often on Athenian walls with graffiti is: “ΧΑΟΣ” (“CHAOS”). It’s just that single word, nothing else around it, and it distills perfectly what the local anarchists have in mind: the complete demolition of every societal structure, the chaos (another Greek word!), the anarchy in its original meaning. If you or other “sophisticated anarchists” have opted to give a different meaning to “ΑΝΑΡΧΙΑ” (“ANARCHY”), good for you, but then this text wasn’t written for you. Then my friend continues:

Two errors: first, the statement that “any society needs structure”, be it a hunter-gatherer one, or a technologically sophisticated one, tells me you didn’t read around half of this page: the section on complex systems (“The necessity of structures, in pictures”); or if you did, you missed the point. The point is that a hunter-gatherer society is much simpler as a complex system than a technologically advanced one, and as such, it requires much simpler structures; so simple that it can be called an anarchic society. So, yes, any society needs structure, but how much structure is the whole point. Your ideal anarchic society is a complex system with billions of members (people), and too little structure, insufficient for its size. Such complex systems don’t seem to exist; you’re going against natural law. The second error is when you say “at any point one can opt out.” No, one can’t. “Out” where? Where is the “out” that one can go? Out into the rest of the non-anarchic world? But how much prophetic ability does it take to realize that the rest of the world won’t allow such a society to exist? Given the first chance, such a powerless, defenseless society will be attacked and taken advantage of by those with enough power to attack it. I know, I already expounded this point in my previous comments, but I’m thinking that perhaps it’s harder for you Americans to grasp it, because you’re so much accustomed to the idea of a fortress-like country. And yet, your fortress is invincible thanks to its military technology. Can you imagine your country completely anarchic, having abandoned its military technology, the research for new weapons and their manufacturing (for I don’t think you’d include those in the A.S.A. — the Anarchic States of America, am I right?) and in spite of that to retain its national sovereignty and anarchic identity? I, for one, can’t. Would you like to hear my opinion about what would happen if you established the A.S.A.? Soon after you brought down the walls of your fortress you’d be invaded by the Mexicans. Do you know how many hungry millions there are in Mexico, who would gladly grab a large piece of your “pie” without sharing with you the anarchic principles of mutual respect and cooperation? Lots! And do you have any idea about the Mexican mafia? Are you aware of how eagerly the Mexican mafiosi would shoot you in order to grab whatever you have, which, anyway, is much more than what they have? So, if you think carefully about all that, I think you’ll agree that a non-anarchic “outside world” must not be allowed to exist; the entire world must suddenly turn into an anarchic society for you to survive, something which is entirely impossible. |

Footnotes:

|

Back to Harry’s index page on social issues